A Turning Point at Haskell

Allan Houser goes boldly into a new chapter

Comrade in Mourning

By Allan Houser, 1948

Auditorium entrance, Haskell Indian Nations University

Lawrence, Kansas

Haskell Indian Nations University spreads gently toward the riparian edges of the Wakarusa River, a tributary of the Kansas River. Much of the campus is gently rolling hills of grass and woodland trails, edged by an active garden and greenhouse. Limestone campus buildings date as far back as 1884; twelve are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Inside the front doors of the recently restored 1933 Auditorium is a quiet watershed moment in American art: Allan Houser’s Comrade in Mourning. Created in 1948, it is both a creative turning point for Houser and his opening salvo as one of the greats in American art.

Houser was born in 1914 in Oklahoma, a member of the Chiricahua band of Apache who had been displaced from the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts of the southwest and Mexico. In 1934 he moved to Santa Fe to study in the Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School, where Dorothy Dunn taught a specific stylization of Native artmaking that for the time was respectful of Indigenous iconography, but was also restrictive. Under her guidance, Houser became a skilled illustrator and painter. Later while living in Los Angeles, he discovered the modernist works of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Isamu Noguchi, and Jean Arp. Artists that would soon have a strong influence over him.

While working as a carpenter in LA, and although he’d only carved with wood a few times and his sculpture experience was limited, Houser answered a call for proposals from the Haskell Alumni Association: they were commissioning a marble sculpture to honor American Indian soldiers on campus. When he won, he found and borrowed tools, purchased a book on sculptural practice, and used a jackhammer for large portions of the piece.

Comrade in Mourning was completed in 1948. At 7 feet tall and on a pedestal, the looming figure is enshrouded in a blanket with a war bonnet at its feet, its stylized face solemn. Like Houser’s earlier work in painting and illustration, Comrade in Mourning is a masterpiece of line and form; the heaviness of the Carrara marble echoes the loft of emotion it is meant to convey. Closer inspection reveals the small chisel marks throughout, which to me belies the large modernist form and makes the sculpture interestingly smooth yet rough and textured, an earthiness exposed depending on where you stand, how the light lands, and the perspective one brings to the piece. I imagine the subject emerging from the earth, abstraction forming forward.

I fully agree with art historian W. Jackson Rushing III, who wrote, “One can scarcely imagine a more successful first attempt at monumental sculpture, for Houser created an aesthetically significant work of art that accomplished what many war memorials do not—a stoic and dignified tribute to heroism that avoids glorifying warfare itself.”

And this is precisely why I love art history: We get the luxury of looking over the course of a lifetime and see the points where history, fate, and perspective turned. Points where one person sees how we look upon the world, what we expect to see, and then suggests another view. There are horrors to war: Picasso and Goya depict them well. But so does Houser, who recognizes the quiet grief of fellow soldiers and a people on the homefront.

But also, when I stand before Comrade in Mourning, I find myself engaged with what this work symbolized for Houser himself: his turn toward his future minimal, modernist voice. It is a radical style change, an exciting pinpoint in one man’s art history. As I get older, it’s these beginnings and endings, chapters in one’s life, that I find the most interesting of all. To see this conical form predict Houser’s upcoming mature and modernist aesthetic, which he will minimalize and abstract over time, is exciting.

The Art World of the time saw it, too. One year after Comrade in Mourning was completed, Houser was awarded the prestigious Guggenheim fellowship. His career as a respected artist was fully launched—he worked and taught, had gallery and museum shows, made a living at it all, and seems to have done well for himself. And yet for the remainder of his life he battled being marginalized as a “Native American artist,” rather than solidly an American artist—or simply an artist contemporary with his peers. This bothered him. Indeed while those artists flirted with Primitivism—an awful term for the use and exploration of folk styles of craft, often characterized by bold lines and flat color—Houser’s heritage gave him a legitimate claim to those styles. Whereas Paul Gauguin or Grant Wood co-opted “primitive” techniques to advance modern art, Hauser’s was within a distinct and fully American artistic language.

Prolific to the end, Houser died in 1994. Today his work is found around the world, including the National Museum of American Art in Washington DC, the Pompidou Center in Paris, and museums across the United States. His was the first major retrospective at the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004.

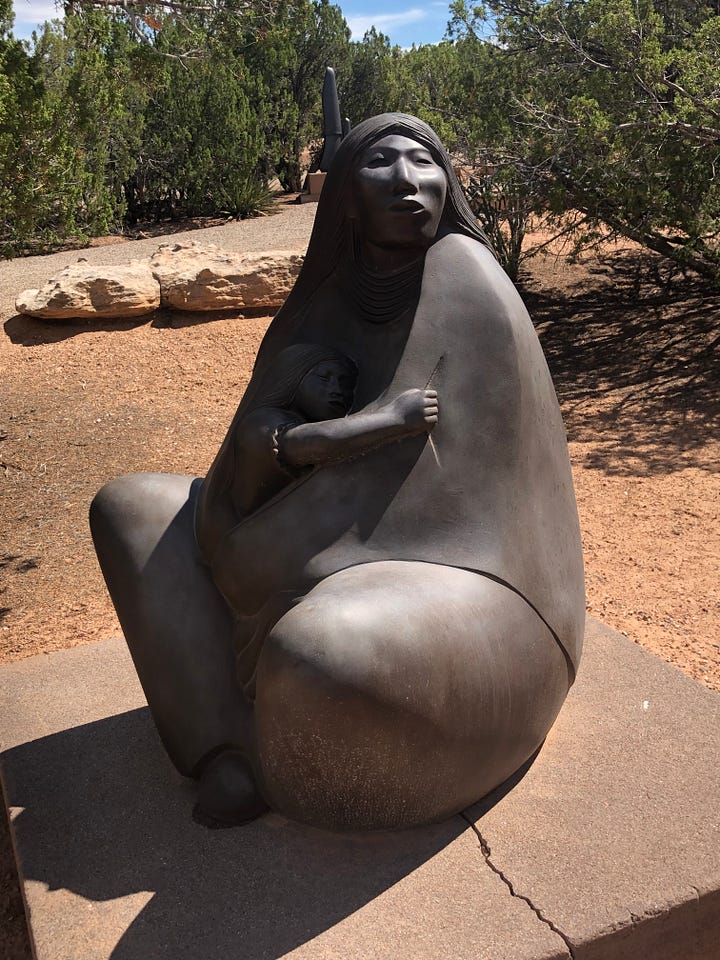

This past summer I visited his studio and sculpture garden, Haozous Place, south of Santa Fe, New Mexico. It is well worth a visit: Houser’s sculptures are beautifully curated among juniper trees and cacti, his diverse styles set in perfect conversation with the landscape. Haozous Place (Haozous is Houser’s family name) is a rare opportunity to see an artist’s breadth of work as he wanted it to be viewed. It puts in strong context a work that has its taproot right here in the Midwest.

My thanks to Travis Campbell, Director of the Haskell Cultural Center & Museum, for sharing his expertise and time during one of my visits.

Visitation Note: The Auditorium is often locked when not in use. I recommend calling the Haskell Cultural Center & Museum to arrange a visit.

Allan Houser’s Comrade in Mourning is currently placed within a series of murals by Haskell alum Franklin Gritts. These scenes of ceremonies, daily life, and history deserve their own article. Until then, be sure to spend time with them when visiting the Haskell Indian Nations University campus.

"As I get older, it’s these beginnings and endings, chapters in one’s life, that I find the most interesting of all. To see this conical form predict Houser’s upcoming mature and modernist aesthetic, which he will minimalize and abstract over time, is exciting."

I love how you layer and collage art, history, and meaning!